Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance profile of Coliform from irrigation water in some selected area of Sokoto State, Nigeria

Abstract

Human activities such as agriculture, domestic sewage disposal, industrial effluent release, urbanization, and poor healthcare waste management significantly contaminate irrigation water. The aim of this study is to detect coliform bacteria, sand their sensitivity profile isolated from irrigation water, the physicochemical analysis of the water samples was studied and recorded neutral across all the sample sites, with 7.18 from Wamakko followed by Tambuwal which recorded 7.17 and the least was from kware with 7.04 which fall within WHO (6.5–8.5) permissible limits. Electrical conductivity was highest in Wamakko (310 μS cm-1) and lowest in Kware (180 μS cm-1). Dissolved oxygen peaked in Tambuwal (6.2 mg L-1), while BOD was highest in Wamakko (5.8 mg L-1). Total dissolved solids and chloride concentrations were also within WHO and SON standards. Heavy metal analysis showed iron levels highest in Wamakko (10.5 mg L-1), copper in Tambuwal (6.4 mg L-1), and zinc in Tambuwal (13.4 mg L-1), with lead detected in all samples (0.4–0.9 mg L-1), exceeding WHO limits of 0.01 mg L-1. Chromium ranged from 2.3 mg L-1 in Wamakko to 4.3 mg L-1 in Kware. Calcium and magnesium concentrations were moderate across all sites. Microbiological analysis revealed presumptive and confirmed coliforms with strong gas production in lactose broth. EMB agar confirmed the presence of Escherichia coli, while MacConkey agar indicated Klebsiella spp. and Enterobacter spp., Salmonella spp. was also isolated from Tambuwal samples. Biochemical tests supported these identifications. Antibiotic susceptibility profiling showed multidrug resistance among isolates: E. coli from Wamakko resisted tetracycline and ampicillin but was sensitive to gentamicin, while Enterobacter spp. from Tambuwal resisted ciprofloxacin and tetracycline. Salmonella spp. exhibited resistance to ampicillin but remained sensitive to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin. These findings indicate contamination of irrigation water with heavy metals and pathogenic coliforms that exceeded WHO standards, posing public health risks and highlighting the need for improved water treatment and monitoring.

Introduction

Water serve as an important resources for agricultural production and in Nigeria, irrigation farming is crucial for ensuring food security and sustaining the lively hoods of a vast population. A large portion of this irrigation water is sourced from surface waters such as rivers, streams, lakes and ponds which are highly susceptible to contamination from various man activity and anthropogenic activities (Akinbile et al., 2015). These activities include the discharge of untreated domestic sewage, agricultural runoff containing animal waste fertilizers and effluents from small-scale industries. Consequently, these water sources often become reservoirs for a plethora of pathogenic microorganisms.

The microbiological quality of irrigation water is a critical determinant of food safety. Fecal contamination introduces enteric pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and parasites which can survive in water and soil and subsequently colonize crops. To assess this risk, microbiological indicators are used with coliform bacteria particularly Escherichia coli (E. coli), serving as the gold standard for indicating recent fecal contamination and the potential presence of more harmful pathogens (Edberg et al., 2000). The detection of high levels of these indicator organisms in water signifies a breach in sanitation and a direct threat to public health.

Studies conducted across Nigeria's geopolitical zones have consistently reported alarming levels of coliform contamination in water sources used for irrigation. For instance, research in South-western Nigeria found coliform counts far exceeding the limits recommended by the World Health Organization for agricultural use (Adeyemi et al., 2024). Similarly, studies in the Northern parts of the country have documented the pervasive presence of fecal coliforms in irrigation canals and reservoirs (Oluwasemire et al., 2020). This wide spread contamination is largely attributed to inadequate sanitation infrastructure, poor waste management systems, and the lack of regulatory enforcement for waste water discharge.

A more worrisome dimension of this public health threat is the emergence and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). The misuse and overuse of antibiotics in human medicine, veterinary care and agriculture have exerted selective pressure leading to the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the environment. Irrigation water contaminated with fecal matter from humans and animals acts as a major conduit for these resistant organisms and their genetic determinants (Chigor et al., 2012). Recent investigations have identified multidrug-resistant E.coli and even extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing strains in Nigerian irrigation water sources (Odetokun et al., 2019). This presents a grave scenario where commonly available antibiotics may fail to treat infections acquired through the consumption of contaminated fresh produce.

When perishable crops like vegetables and fruits crops are irrigated with such contaminated water, they can become contaminated with these resistant bacteria. Consumption of raw or inadequately washed produce then becomes a direct route of transmission for resistant pathogens into the human gut. This can lead to difficult-to-treat infections; longer hospital stays higher health care costs and increased mortality (Okeke et al., 2021). Therefore, the issue transcends mere agricultural practice and sits at the intersection of environmental health, food safety and clinical medicine.

Despite the growing body of evidence, there remains a need for comprehensive and concurrent assessment of both the quantitative microbial load and the antibiotic susceptibility patterns of isolates from irrigation water across diverse agricultural regions in Nigeria. Such a study is vital to fully appreciate the scope of the problem, identify prevalent resistance patterns, and provide a scientific basis for targeted interventions. This research is designed to address this gap providing critical data that can inform policy, guide regulatory standards and ultimately contribute to safe guarding public health and ensuring the safety of the Nigerian food supply.

Material and Methods

Study area

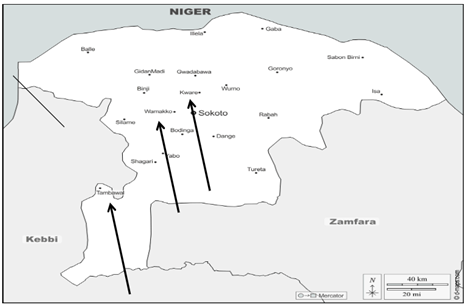

Sokoto State is situated in north-western Nigeria within the Sudan Savannah ecological zone, between latitude 12°00′N–13°58′N and longitude 4°08′E–6°54′E. It shares an international boundary with the Republic of Niger to the north, Kebbi State to the west and south-west, and Zamfara State to the east and south-east. The state experiences a semi-arid climate with average rainfall of 500–750 mm annually and a prolonged dry season from October to May. Its economy is mainly agrarian, relying on irrigation farming, livestock rearing, and trading.

Kware, Wamakko, and Tambuwal LGAs were selected for this study due to their heavy reliance on irrigation farming (Fig. 1). Kware LGA located at approximately 13°12′N latitude and 5°16′E longitude, had a population of 133,899 in 2006, projected above 280,000 by 2025, with the Hausa-Fulani as the dominant tribe. Its people are mainly farmers and traders, cultivating rice, onions, tomatoes, and vegetables. Wamakko LGA lying at coordinates 13°03′N latitude and 5°07′E longitude, with a population of 179,619 in 2006 and estimated above 340,000 in 2025, is semi-urban and hosts Usmanu Danfodiyo University. Its people engage in farming, livestock rearing, trading, and petty businesses, with crops like millet, sorghum, and rice cultivated. Tambuwal LGA is located at coordinates 12°24′N latitude and 4°39′E longitude, had 224,931 people in 2006, and projected above 360,000 in 2025, dominated by Hausa-Fulani. The people practice irrigation and rain-fed farming, livestock trading, and small-scale businesses, with rice, pepper, and okra as common crops, and a major weekly market serving as a hub for trade.

Fig. 1: Map of Sokoto State showing the study areas

Sample collection

A total of three water samples were collected, one from each of Kware, Wamakko, and Tambuwal LGAs of Sokoto State. The samples were collected from irrigation sources commonly used by farmers, such as rivers, lakes and streams. Collection was done using sterile 500 ml glass bottles that had been autoclaved at 121°C for 15 minutes. During sampling, bottles were rinsed with the water source before being filled at a depth of 15–30 cm to avoid surface contaminants. The bottles were tightly capped, labelled with the location and date, and placed in an ice-packed cooler. Samples were transported under cold conditions (4–8°C) to the Microbiology Laboratory of Sokoto State University, Sokoto, where they were processed within six hours for coliform detection and antibiotic sensitivity analysis.

Physicochemical analysis of the water samples

The physicochemical parameters of the water samples were analyzed following the procedures outlined by Greenberg et al. (1995). Parameters such as Electrical conductivity, TDS, TSS, BOD, COD, calcium, magnesium, dissolved oxygen, and various forms of alkalinity (carbonate, bicarbonate, and chloride) were determined using standard titrimetric and colorimetric techniques as described by (APHA et al., 2023).

Heavy metal analysis

The concentrations of selected heavy metals, namely zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), chromium (Cr), lead (Pb), and copper (Cu), was determined using Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), in accordance with the methods described by James et al. (2023).

Coliforms detection

Presumptive test

The presumptive test was carried out by inoculating 10 mL, 1 mL and 0.1 mL of the water samples into test tubes containing 10 mL of MacConkey broth with inverted Durham tubes, incubated at 35–37 °C for 24–48 hours. Gas production and color change indicated possible coliform presence (APHA, 2017).

Confirmed test

Colonies from the positive presumptive tubes, a loopful was streaked onto Eosin Methylene Blue (EMB) agar plates and incubated at 35–37 °C for 24 hours. Colonies showing green metallic sheen (indicative of E. coli) or dark-centered colonies (other coliforms) were considered positive.

Completed test

A colony from EMB agar was inoculated into lactose broth with Durham tubes and on nutrient agar slants. Gas production in lactose broth and Gram staining of nutrient agar cultures were performed. Gram-negative, non-spore forming rods confirmed coliform identity (APHA, 2017).

Biochemical characterization of the bacterial isolates

Following gram staining as described by Cheesebrough (2006), biochemical tests were conducted to characterize the different bacteria; isolates the following test were carried out indole, methyl Red-Voges Proskauer (MRVP) and citrate utilization.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

The antibiotic sensitivity of bacterial isolates was determined using the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method on Mueller–Hinton agar, following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2023) guidelines. Pure colonies of the isolates were suspended in sterile saline and adjusted to 0.5 McFarland turbidity standards. Sterile swabs were used to evenly spread the suspension across the surface of the agar plates.

Commercial antibiotic discs representing commonly used classes, including ciprofloxacin (5 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), ampicillin (10 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), ceftriaxone (5 µg), and chloramphenicol (30 µg), were aseptically placed on the agar surface using sterile forceps. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 18–24 hours, after which zones of inhibition around each disc were measured in millimeters. The results were interpreted as sensitive, intermediate, or resistant according to CLSI breakpoints.

Results and Discussion

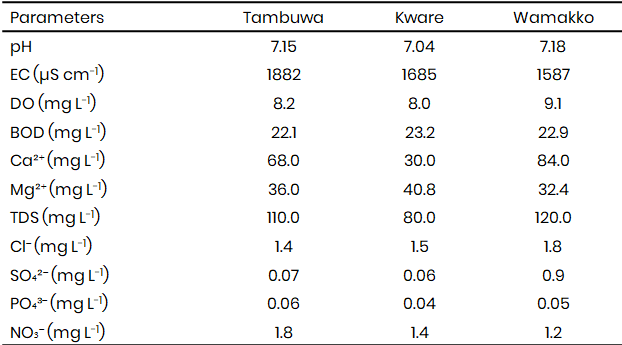

The physicochemical parameters (Table 1) studied showed that the pH values of irrigation water samples from Tambuwal (7.15), Kware (7.04), and Wamakko (7.18) fall within the permissible range of 6.5–8.5 recommended by WHO and SON, indicating that the water is suitable for agricultural use in terms of acidity and alkalinity. Electrical conductivity (EC) values, however, were high (1882 µS cm-1 in Tambuwal, 1685 µS cm-1 in Kware, and 1587 µS cm-1 in Wamakko), exceeding the WHO and FAO recommended limits of ≤1000 µS cm-1 and 750 µS cm-1, respectively. Elevated EC reflects high salinity, which could pose a risk to soil structure and crop productivity, this is in agreement with reports by Oladipo et al. (2022) that high conductivity levels in irrigation water reduce soil permeability and affect crop yield.

Dissolved oxygen (DO) ranged between 8.0–9.1 mg L-1, above the minimum guideline of 5 mg L-1, suggesting adequate aeration to support microbial and biochemical activities in the aquatic environment. However, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) values were exceptionally high (22.1–23.2 mg L-1), far above the <3 mg L-1 permissible limit. High BOD implies heavy organic pollution, possibly from agricultural runoff, sewage, or animal wastes. Similar findings were reported by Abubakar and Musa (2021), who linked high BOD in irrigation sources in northern Nigeria to poor waste management. Calcium and magnesium concentrations (Ca: 30–84 mg L-1, Mg: 32.4–40.8 mg L-1) were within acceptable ranges for irrigation water, while TDS values (80–120 mg L-1) were lower than the 1000 mg L-1 limit, suggesting minimal dissolved solids content. Chloride, sulphate, and phosphate levels were all below WHO and FAO thresholds, making them less problematic for irrigation.

Table 1: Physicochemical characteristics of irrigation water samples

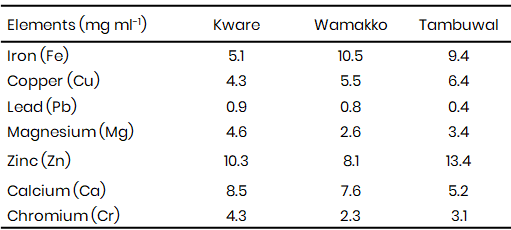

The heavy metal concentration (Table 2) showed that the concentrations of iron, copper, lead, zinc, and chromium in all samples were far above WHO and SON permissible limits, indicating serious contamination. Iron ranged from 5.1–10.5 mg L-1 against the 0.3 mg L-1 limit, which is consistent with the findings of Lawal et al. (2020), who reported elevated iron in irrigation water from Sokoto metropolis due to effluents from automobile workshops and open dumping. Copper levels (4.3–6.4 mg L-1) also exceeded the 2.0 mg L-1 standard, in agreement with the same study, where high copper concentrations were linked to indiscriminate disposal of metallic wastes.

Lead concentrations (0.4–0.9 mg L-1) were particularly alarming, being several times higher than the 0.01 mg L-1 safe limit, suggesting potential risks of bioaccumulation in crops irrigated with such water. A similar observation was made by Abubakar and Garba (2021) in Wurno and Goronyo LGAs of Sokoto, where lead contamination in irrigation water and vegetables was also above WHO limits. Chromium levels (2.3–4.3 mg L-1) were higher than the 0.05 mg L-1 permissible limit, raising concern over carcinogenic exposure. This is comparable to the findings of Sharma et al. (2023) in Punjab, India, who associated elevated chromium in irrigation water with industrial effluents.

Zinc concentrations (8.1–13.4 mg L-1) also exceeded the WHO permissible level of 3 mg L-1, though SON allows up to 5 mg L-1. This observation aligns with Oko et al. (2022), who reported elevated zinc levels in irrigation water from Enugu State due to mining activities. Magnesium (2.6–4.6 mg L-1) and calcium (5.2–8.5 mg L-1) concentrations in this study were within acceptable thresholds, which is in line with FAO guidelines for irrigation water. These patterns demonstrate that heavy metal contamination is not peculiar to Sokoto but a recurring issue in agricultural water sources across developing regions.

Table 2: Heavy metals concentrations in irrigation water (mg L-1)

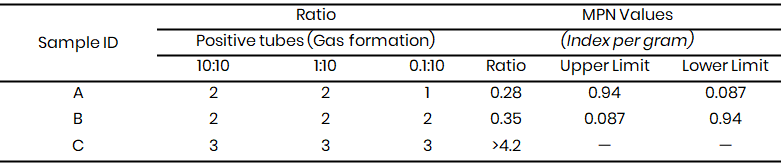

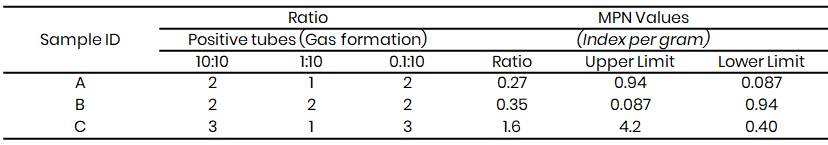

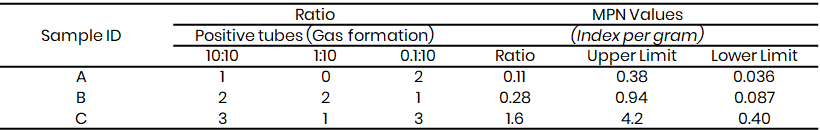

Microbiological Analysis of the water sample showed that the presumptive test (Table 3 - 8) confirmed the presence of coliform bacteria across the three study sites, with gas production observed in Durham tubes. The Most Probable Number (MPN) values, which ranged from 0.11 to >4.2, exceeded acceptable microbial safety thresholds, this showed faecal contamination and poor water quality for irrigation. This observation agrees with the findings of Lawal and Musa (2022) in Sokoto metropolis, which also detected high coliform counts in irrigation water samples and linked them to direct discharge of sewage and animal waste into open water bodies.

At Kware (Table 3 & 6), MPN values reached >4.2 in some samples, indicating heavy contamination. A similar report was made by Yahaya et al. (2020) in Birnin Kebbi, where high coliform loads were observed in irrigation canals receiving untreated effluents. In Wamakko (Table 4 & 7), MPN values of up to 1.6 were recorded, consistent with the results of Suleiman et al. (2022), who reported that irrigation water from local streams contained unsafe levels of faecal coliforms due to nearby livestock rearing. Tambuwal samples (Table 5 & 8) also showed MPN indices ranging from 0.11 to 1.6, comparable to observations by Singh et al. (2021) in India, where faecal contamination in irrigation water was linked to poor sanitation and open defecation practices.

Table 3: Presumptive coliform test results for Kware

Table 4: Presumptive coliform test results for Wamakko

Table 5: Presumptive coliform test results for Tambuwal

Table 6: Presumptive coliform test results for Kware

Table 7: Presumptive coliform test results for Wamakko

Table 8: Presumptive coliform test results for Tambuwal

The presence of coliforms in all three locations indicates a high risk of contamination of irrigated vegetables, thereby posing health threats to consumers. This aligns with the general conclusion of Abubakar and Garba (2021), who emphasized that untreated irrigation water is a major pathway for pathogen transfer to food crops in Sokoto and other parts of Nigeria.

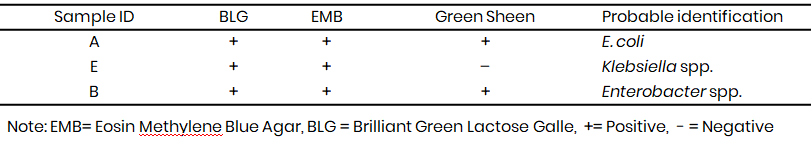

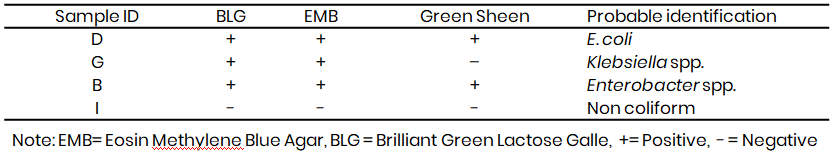

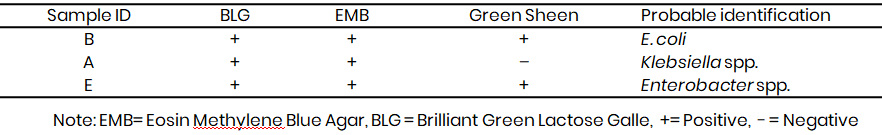

The confirmed test results on Eosin Methylene Blue (EMB) and MacConkey agar revealed the presence of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., and Enterobacter spp. across Kware, Wamakko, and Tambuwal LGAs. Colonies showing a green metallic sheen on EMB, characteristic of E. coli, were consistently observed, and this finding corresponds with Lawal and Musa (2022), who also reported frequent E. coli isolation from irrigation water in Sokoto metropolis, attributing contamination to faecal seepage and poor sanitation. The presence of Klebsiella spp. was confirmed by pink colonies on MacConkey agar, a result similar to Abubakar and Garba (2021), who detected Klebsiella in irrigation water and vegetables from Wurno LGA, suggesting the persistence of this bacterium in agricultural environments. Enterobacter spp. were also isolated across the three LGAs, consistent with observations by Oko et al. (2022) in Enugu State, where Enterobacter was a recurrent contaminant of irrigation canals due to sewage discharge. The occurrence of non-coliforms in some Wamakko samples further indicates diverse microbial pollution, which Sharma et al. (2023) also described in Punjab, India, where irrigation water was contaminated with both coliforms and opportunistic pathogens from industrial effluents.

Gram staining confirmed that the isolates were predominantly Gram-negative rods, appearing pink under the microscope, which corresponds to the characteristics of coliforms. The observation of E. coli, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter spp. as Gram-negative bacilli agrees with Lawal et al. (2020), who similarly found Gram-negative enteric rods dominating irrigation water samples in Sokoto. The variations in arrangement, with some bacteria occurring in chains, pairs, or clusters, further reflect the normal morphological diversity of coliforms, which Abubakar and Garba (2021) also reported in their microscopic characterization of irrigation water isolates from Sokoto. The absence of Gram-positive bacteria in this study highlights that contamination was primarily of enteric origin, a finding consistent with Oko et al. (2022), who reported that Gram-negative enteric rods were the dominant contaminants of irrigation waters in southeastern Nigeria. Likewise, Sharma et al. (2023) in India observed similar Gram-negative predominance in irrigation canals, linking it to faecal and industrial effluent pollution.

The Gram staining results from Wamakko samples showed that all isolates were Gram-negative rods, appearing pink under the microscope and arranged mostly in pairs, clusters, and chains. This finding is typical of coliform bacteria and corresponds with earlier reports by Lawal and Musa (2022), who also documented Gram-negative rod predominance in irrigation water isolates from Sokoto metropolis, linking them to faecal contamination. The presence of rod-shaped organisms with diverse arrangements further reflects the morphological diversity of enteric bacteria, a pattern that Abubakar and Garba (2021) similarly observed in water and vegetable samples from Wurno LGA.

In Tambuwal samples, most isolates were Gram-negative rods arranged in chains, pairs, and clusters, although Gram-positive cocci were also detected. The presence of cocci suggests possible contamination from skin flora or other environmental sources, which aligns with the findings of Oko et al. (2022) in Enugu State, where both enteric Gram-negative rods and Gram-positive cocci were recovered from irrigation canals. Additionally, the occurrence of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative rods in this study agrees with Sharma et al. (2023), who reported that irrigation water in Punjab, India, harboured mixed microbial populations due to inputs from sewage and agricultural runoff.

The biochemical characterisation of isolates from Kware, Wamakko, and Tambuwal confirmed the presence of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., Staphylococcus spp., and Streptococcus spp. The detection of E. coli through positive indole, citrate, and motility tests corresponds with the Gram staining and culture results, reinforcing its role as a faecal indicator organism. Similar biochemical profiles of E. coli have been reported in irrigation waters in Sokoto and neighbouring states (Lawal et al., 2020). The isolation of Klebsiella spp. and Enterobacter spp., both positive for citrate utilisation and urease, is consistent with the work of Abubakar and Garba (2021), who recovered these organisms from irrigation water and vegetables in Sokoto, suggesting widespread environmental persistence of coliforms in the region.

The identification of Staphylococcus and Streptococcus sp., characterised by catalase and coagulase reactions, indicates contamination from non-enteric sources such as human handling or animal activities near irrigation sites. This agrees with Oko et al. (2022), who reported similar findings in southeastern Nigeria, where both enteric and non-enteric organisms were recovered from water used for vegetable farming. The detection of mixed coliforms and non-coliforms in this study mirrors observations by Sharma et al. (2023) in India, where biochemical tests revealed diverse bacterial populations in irrigation canals contaminated by both sewage and agricultural effluents. Overall, the biochemical results complement the Gram staining and culture outcomes, demonstrating that irrigation waters in Kware, Wamakko, and Tambuwal are reservoirs of potentially pathogenic bacteria with both faecal and environmental origins. These might be due to attributed to poor hygiene and sanitation such as defecation, washing, bathing around the river which are common practices in the study area.

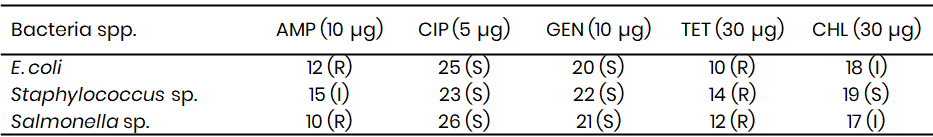

The antibiotic susceptibility test results revealed that isolates from sachet water across Kware, Wamakko, and Tambuwal exhibited varying levels of resistance and sensitivity to the antibiotics tested (Tables 9 – 11). In Kware (Table 9), E. coli showed resistance to ampicillin (12 mm) and tetracycline (10 mm), but was sensitive to ciprofloxacin (25 mm) and gentamicin (20 mm), while displaying an intermediate response to chloramphenicol (18 mm). This trend of resistance to ampicillin and tetracycline by E. coli has been widely reported in Nigeria, with Okeke et al. (2021) noting similar patterns in environmental isolates, attributing the resistance to the overuse of these antibiotics in both human and veterinary medicine. The sensitivity to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin is in agreement with findings by Yusuf et al. (2023), who reported these antibiotics as the most effective against E. coli from drinking water sources.

Table 9: Antibiotic sensitivity pattern of Bacteria spp. from Kware (Zone of inhibition in mm)

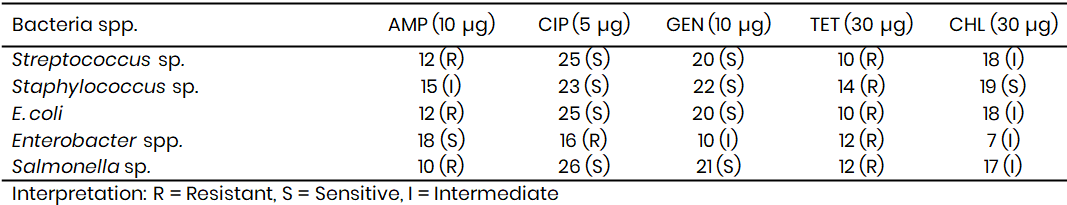

Table 10: Antibiotic sensitivity pattern of Bacteria spp. from Wamakko (Zone of inhibition in mm)

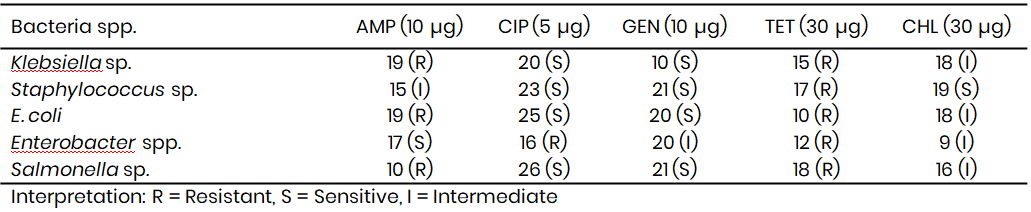

Table 11: Antibiotic sensitivity pattern of Bacteria spp. from Tambuwal (Zone of inhibition in mm)

Staphylococcus spp. from Kware demonstrated intermediate resistance to ampicillin (15 mm), sensitivity to ciprofloxacin (23 mm), gentamicin (22 mm), and chloramphenicol (19 mm), but resistance to tetracycline (14 mm). A comparable observation was made by Olanrewaju et al. (2022), who found that Staphylococcus spp. isolated from sachet water were consistently resistant to tetracycline but susceptible to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin, reinforcing the persistence of these resistance trends in local water supplies. Similarly, Salmonella spp. in Kware was resistant to ampicillin and tetracycline yet sensitive to ciprofloxacin (26 mm) and gentamicin (21 mm), reflecting findings by Adeyemi et al. (2022), who documented resistance to first-line antibiotics in Salmonella isolates from food and water in southwestern Nigeria.

In Wamakko (Table 10), Streptococcus spp. isolates showed resistance to ampicillin (12 mm) and tetracycline (10 mm), but sensitivity to ciprofloxacin (25 mm) and gentamicin (20 mm), with intermediate resistance to chloramphenicol (18 mm). This agrees with the findings of Shittu and Bello (2020), who observed a similar sensitivity profile of Streptococcus spp. in contaminated wells, where ciprofloxacin remained the most effective drug. Staphylococcus spp. in Wamakko followed the same trend as in Kware, being resistant to tetracycline but sensitive to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin, a trend echoed by Adeyemo et al. (2021) in their study of sachet water in Lagos.

Interestingly, Enterobacter spp. in Wamakko displayed sensitivity to ampicillin (18 mm) but resistance to ciprofloxacin (16 mm), alongside intermediate resistance to gentamicin (10 mm) and chloramphenicol (7 mm). This pattern indicates emerging multidrug resistance, a finding consistent with Olanrewaju et al. (2022), who also reported ciprofloxacin-resistant Enterobacter spp. in sachet water samples from Sokoto, suggesting possible horizontal gene transfer of resistance traits in environmental settings. E. coli and Salmonella spp. in Wamakko mirrored the resistance profiles observed in Kware, strengthening the evidence of widespread resistance to older antibiotics across the region.

Tambuwal (Table 11) isolates revealed similar resistance dynamics. Klebsiella spp. was resistant to ampicillin (19 mm) and tetracycline (15 mm), but sensitive to ciprofloxacin (20 mm) and gentamicin (10 mm), with intermediate sensitivity to chloramphenicol (18 mm). These results are in line with the findings of Nworie et al. (2021), who observed multidrug resistance in Klebsiella spp. isolated from drinking water, where ciprofloxacin remained one of the few effective drugs. Staphylococcus spp. and E. coli isolates from Tambuwal also exhibited resistance to ampicillin and tetracycline, but sensitivity to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin, a pattern consistent with national surveillance reports on antimicrobial resistance in environmental samples (Yusuf et al., 2023). Moreover, Enterobacter spp. from Tambuwal showed resistance to ciprofloxacin (16 mm) and tetracycline (12 mm), while expressing intermediate resistance to gentamicin (20 mm) and chloramphenicol (9 mm).

This multidrug resistance reflects the trends seen in Wamakko and corresponds with global concerns highlighted by WHO (2022), which noted that Enterobacter spp. is increasingly recognised as an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen in low-resource settings. Salmonella spp. from Tambuwal was also resistant to ampicillin and tetracycline, but sensitive to ciprofloxacin (26 mm) and gentamicin (21 mm), echoing reports by Adeyemi et al. (2022) that ciprofloxacin remains effective against Salmonella spp. despite the widespread resistance to other drugs.

Conclusion

Water sources for irrigation farming in this study contained high level of bacterial pathogens which are indicators of feacal contamination mostly E. coli and Klebsiella which indicate serious health threat, unsuitable for agricultural use. Government should conduct surveillance and regular monitoring of these water bodies in order to provide good quality and microbiologically safe water for this purpose, farmers and riverine communities should be encourage to practice sanitation mostly open defecation to ensure human health and protect against widespread of waterborne illnesses.

References

Abubakar, A., & Garba, I. (2021). Heavy metal and microbial contamination of irrigation water and vegetables in Wurno and Goronyo Local Government Areas of Sokoto State, Nigeria. Journal of Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(3), 112–121.

Adeyemi, O. J., Fashola, A. O., Oladimokeke, U., & Danjuma, S. (2024). Antibiotic-resistant bacteria in irrigation water: Emerging threats to food safety. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 36, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.jgar.2024.05.006

Akinbile, C. O., Yusoff, M. S., & Ahmad, R. (2015). Environmental impact of irrigation water quality on food safety in Nigeria. Agricultural Water Management, 152, 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2015.01.009

APHA - American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, & Water Environment Federation. (2023). Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater (24th ed.). American Public Health Association.

APHA - American Public Health Association. (2017). Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater (23rd ed.). APHA.

Cheesbrough, M. (2006). District laboratory practice in tropical countries (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chigor, V. N., Umoh, V. J., & Smith, S. I. (2012). Waterborne pathogens and antimicrobial resistance in Nigeria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(4), 1507–1519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9041507

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. (2023). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (33rd ed.). CLSI supplement M100. CLSI.

Edberg, S. C., Rice, E. W., Karlin, R. J., & Allen, M. J. (2000). Escherichia coli: The best biological drinking water indicator for public health protection. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 88(S1), 106S–116S. https://doi.org/10.1111 /j.1365-2672.2000.tb05338.x

Greenberg, A. E., Clesceri, L. S., & Eaton, A. D. (Eds.). (1995). Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater (19th ed.). American Public Health Association; American Water Works Association; Water Environment Federation.

Copyright

Open Access: This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.