Determination of optimum maturity of Mabrouka mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruits based on biochemical and sensory properties

Abstract

An experiment to determine optimum maturity of Mabrouka mango fruits on the basis of biochemical and sensory parameters was conducted in Benue State in 2018. Selected mango orchards from three Local Government Areas (LGAs) of the state - Gboko, Konshisha, Otukpo - were used for the study. Fruit maturity stages were defined based on weeks after flowering (WAF). Thus the 6 stages were 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and 26 WAF. The experiment was a 3 × 6 factorial arranged in completely randomized design (CRD). Factors were location (3) and maturity stage of fruit (6). Biochemical and sensory attributes were evaluated. Results indicated significant influence of location on TSS and pH with fruits from Gboko recording significantly higher values of these parameters. TSS and pH also increased with increase in number of weeks after flowering. Crude protein, crude fibre and carbohydrate decreased with advance in fruit maturity from 21 to 26 WAF. Conversely, ash and moisture contents increased with increase in weeks after flowering. Sensory properties evaluated did not respond significantly to location except peel colour. Most of the sensory traits responded to fruit ripening stage, increasing with increase in number of weeks after flowering, although not to the same extent. Fruits harvested 25 WAF had the highest overall acceptability scores. Sensory traits also improved when fruits were stored. It is conclusive that for best sensory traits and TSS, fruits should be harvested 25 to 26 WAF although there may be less carbohydrate and protein contents.

Introduction

Mango (Mangifera indica L.) is one of the most popular fruits consumed world-wide (Evans and Ballen, 2012) with over 1000 known varieties and commercial production in 87 countries (Tharanathan et al., 2006). Mango is the fifth largest fruit crop produced worldwide after banana, grapes, apples and oranges (Bally et al., 2009; Okoth et al., 2013a). It is one of the most extensively exploited fruits for food, juice, flavour, fragrance and colour and a common ingredient in new functional foods often called super fruits (Kittiphoom, 2012). Mango fruit contains almost all the known vitamins. It is an excellent source of pro-vitamin A, necessary for sustenance of a healthy skin. Mango contains high concentrations of phytochemicals, including gallic acid, mono galloyl glucosides, gallotannins, flavonol glycosides and benzophenone derivatives (Schieber et al., 2000); some of which are unique to the plant and have been proposed for use in creating phytochemical rich dietary supplements (Barreto et al., 2008). Ripe mangoes are processed into frozen mango products, canned products, dehydrated products, and ready-to-serve beverages (Ramteke and Eipeson, 1997; Kittiphoom, 2012).

In spite of the importance of mango, huge losses are experienced yearly due to wrong time of harvesting, poor harvesting, poor handling and poor storage techniques. Lack of proper knowledge of fruit maturity is considered to be one of the major problems contributing to post-harvest losses in mango (Gitonga et al., 2010).

The post-harvest behaviour of mango is generally influenced by the maturity of the fruit at harvest. In most fruits, quality is maximized when the fruits are harvested more mature or ripe, whereas shelf and storage life are extended if they are harvested less mature or unripe (Toivonen, 2007; Ambuko et al., 2014). Fruits harvested prematurely especially those targeting distant markets fail to attain optimal sensory attributes which affects consumer acceptance. Also, their shelf life is very short because they are highly susceptible to mechanical damage (Yahia, 2011). The quality and consistency of processed products such as juices, pulps, jams and dehydrated or dried products is affected by quality of fruits which is in turn affected by harvest maturity amongst other factors. As the fruits change from mature green stage to tree ripe stage and during storage, various physical and physiological changes occur and this may affect the quality of both fresh and processed mango products (Brecht et al., 2009). Farmers often use subjective maturity indices based on visual judgement of size, peel and flesh colour, peel gloss etc but maturity determination based on visual observation is unreliable and also prone to errors because the subjective indices are affected by factors such as production location, variety and cultural practices.

Harvesting at the right maturity stage is critical for all mango value chain actors to ensure high quality of fresh fruits and processed mango products which is critical for market access and consumer acceptance. For the farmers, knowledge of maturity indices will guide them to harvest at the right stage for the target market and/or use, thereby minimizing rejections at the market stage and reducing losses. Amongst the mango varieties cultivated in Benue State, Mabrouka is one of the most sought after variety due to its unique sweetness, richness, flavour, considerable shelf life and high market value. Nevertheless, high losses have been experienced along the supply chain due to wrong harvesting stage amongst other factors. It is important that maturity indices be established for cultivars, growing regions and purpose of harvest (immediate consumption, local or export markets, storage, etc). It is both necessary and very common that several indices be used together in a complimentary manner to make a better decision. Information on the appropriate maturity stage of Mabrouka in Benue State and Nigeria at large is scarce if not lacking. Considering the position of Benue state in mango production in Nigeria, there is a pressing and urgent need to determine the appropriate harvesting stage of Mabrouka so as to improve its sensory and nutritional quality, extend its storage life and facilitate marketing. This study was therefore carried out to determine the most appropriate harvesting stage for Mabrouka fruit on the basis of biochemical and sensory attributes.

Material and Methods

Mango orchards were selected in three Local Government Areas of Benue State in Southern Guinea Savannah of Nigeria. The Local Government Areas are Konshisha (Latitude 7º 01'47.75'' N, Longitude 8º 39'37.33'' E) Otukpo (Latitude 7º 16' 1.06'' N, Longitude 8º 04'3.50''E) and Gboko (Latitude 7º 18' 58.18'' N, Longitude 8º 54’6.01” E). From each of the farms in each location, five mango trees of similar vigour and age were selected and tagged at 50% flowering. The number of days from 50% flowering to physiological maturity (mature green stage), based on flesh colour defined by yellowing of the flesh around the seed was established as stage one (1) [21 weeks after flowering (147 days after flowering)]. Subsequent stages were stage two (2)[22 weeks after flowering (154 days after flowering)], stage three (3)[23 weeks after flowering (161 days after flowering)], stage four(4)[24 weeks after flowering (168 days after flowering)], stage five (5)[25 weeks after flowering (175 days after flowering)] and stage six(6)[26 weeks after flowering (182 days after flowering)] were take seven (7) days apart. At each harvest date, 10 fruits were harvested from each sampled tree using a cloth bag attached to a long pole. The fruits were immediately washed in water containing 1% acetic acid for disinfection. Only uniform fruits were selected. Selected fruits from each mango tree in the same location were combined and divided into two lots of 25 fruits each for biochemical analyses immediately after harvest as well as after storage. Determinations of biochemical attributes were done in the Chemistry and Biological Sciences laboratories of Benue State University Makurdi.

The experiment was a factorial combination of location and fruit ripening stage laid out in Completely Randomized Design (CRD) and replicated three times. The three locations were Konshisha, Gboko and Otukpo. The six fruit maturity stages were 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and 26 weeks after flowering (WAF).

Biochemical analysis

Relevant biochemical parameters were evaluated. Total Soluble Solids (TSS) content of the juice extracted from the fruits (from each location and maturity stage) was determined using a hand refractometer. The mean TSS level was expressed as % brix.

Total Titratable Acidity (TTA) of mango fruits was estimated by titrating a known volume of juice obtained from the fruits of all the treatments against standard sodium hydroxide solution (0.1 N) using phenolphthalein as an indicator. The acidity of fruits so obtained was expressed as grams of anhydrous citric acid per 100 g of pulp. The TTA was expressed as % citric acid equivalent using the formula;

Acidity Percentage ꞊ Sample reading (ml) × Dilution factor (0.0064) × 100 ÷ sample weight (ml).

pH value in fruit juice were measured directly using a pH meter.

Proximate analysis (crude protein, crude fibre, crude fat, moisture and ash contents) were done according to AOAC (1995) methods while carbohydrate percentage was evaluated as follows;

Carbohydrate (%) = 100 – (% Moisture + % Protein + % Crude fibre + % Crude fat + % Ash content).

Sensory analysis

Sensory evaluation of fruits was done using 20 panellists of different gender and age. The observations were recorded when the fruits were just harvested and when 75% of the fruit was ripened. Mango was compared from different locations and maturity stages for texture, colour, flavour, taste and overall acceptability. Sensory evaluation was done using a nine point hedonic scale where 9 = like extremely; 8 = like very much; 7 = like moderately; 6 = like slightly; 5 = neither like nor dislike; 4 = dislike slightly; 3 = dislike moderately; 2 = dislike very much; 1 = dislike extremely. The ratings for the sensory attributes were as described by Ihekoronye and Ngoddy (1985).

Statistical analysis

Data obtained from the study was subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using GENSTAT statistical package. Means were separated using Fisher‘s Least Significance Difference (F-LSD) at 5% level of probability.

Results and Discussion

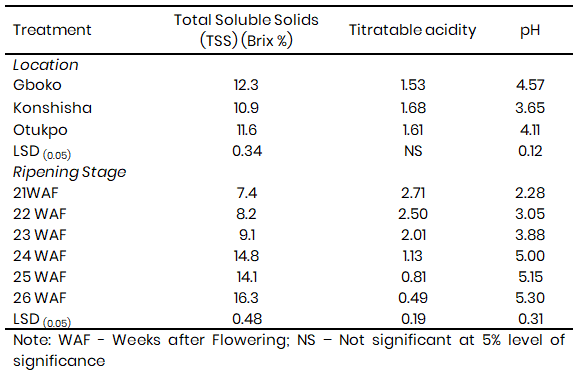

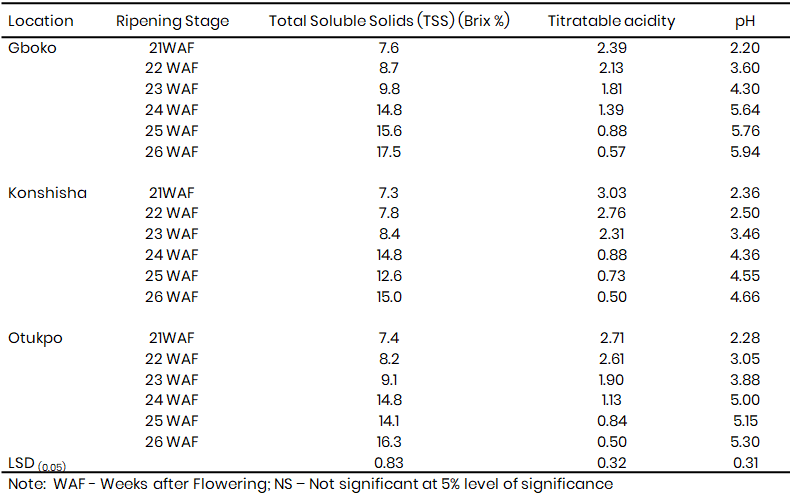

A summary of main and interaction effects of location and maturity stage on some biochemical properties of Mabrouka fruit in Benue State is presented in Table 1 and 2 respectively. Location exerted significant effect on TSS and pH with the Gboko location giving significantly higher values of the two parameters. The least of the values were from the Konshisha fruits. On the other hand, fruit maturity stage showed significant influence on all the three parameters evaluated viz: TSS, TA and pH. While TSS and pH showed increasing values with advance in maturity, that is weeks after flowering, TA adopted the opposite trend. Generally, interaction of location and maturity stage showed that TSS and pH values increased with maturity level of fruits while for TA, the reverse was the case. However, the magnitude of the variation in values of the traits was not the same across locations.

Table 1: Main effect of location and ripening stage on some biochemical properties of Mabrouka mango fruits in Benue State, Nigeri

Table 2: Interaction effect of location and ripening stage on dry matter and biochemical properties of Mabrouka mango fruits in Be

Data gotten from proximate analysis of Mabrouka showed that crude fibre decreased with increase in maturity stage. Fruits harvested at 21weeks after flowering gave the highest crude fibre. Fruits harvested in Konshisha at 21 weeks after flowering gave the highest crude fibre. The lowest crude fibre was obtained from fruits harvested in Konshisha at 26 weeks after flowering (Fig. 1).

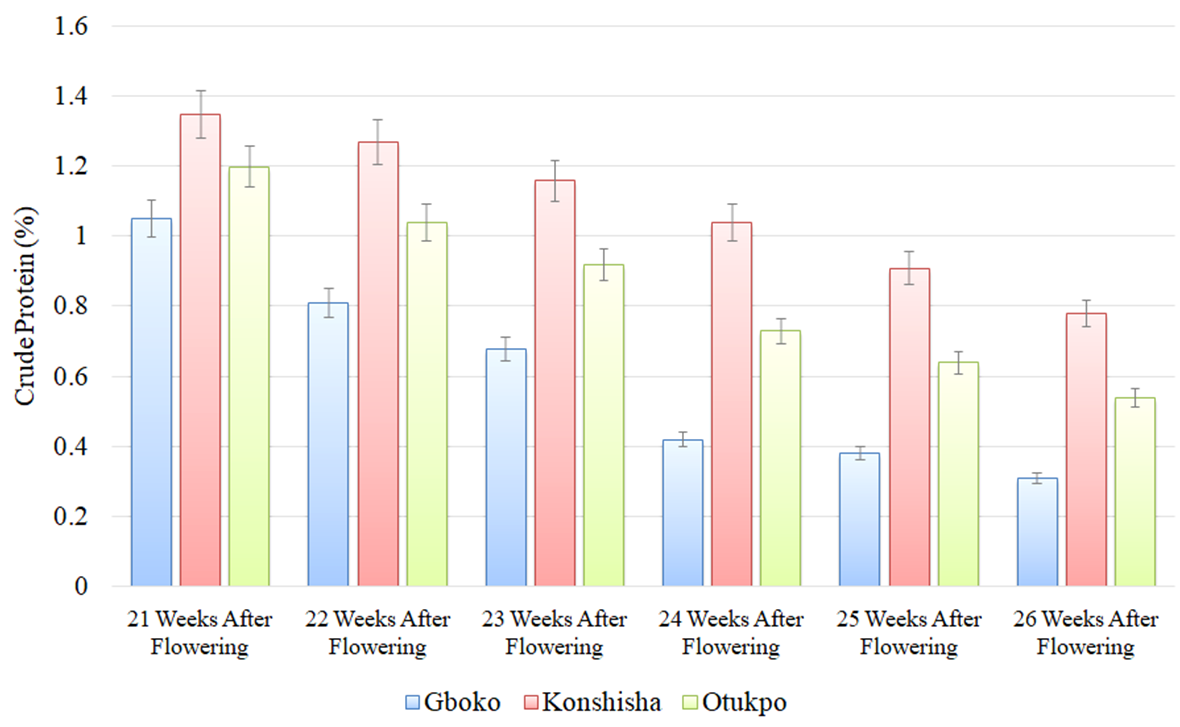

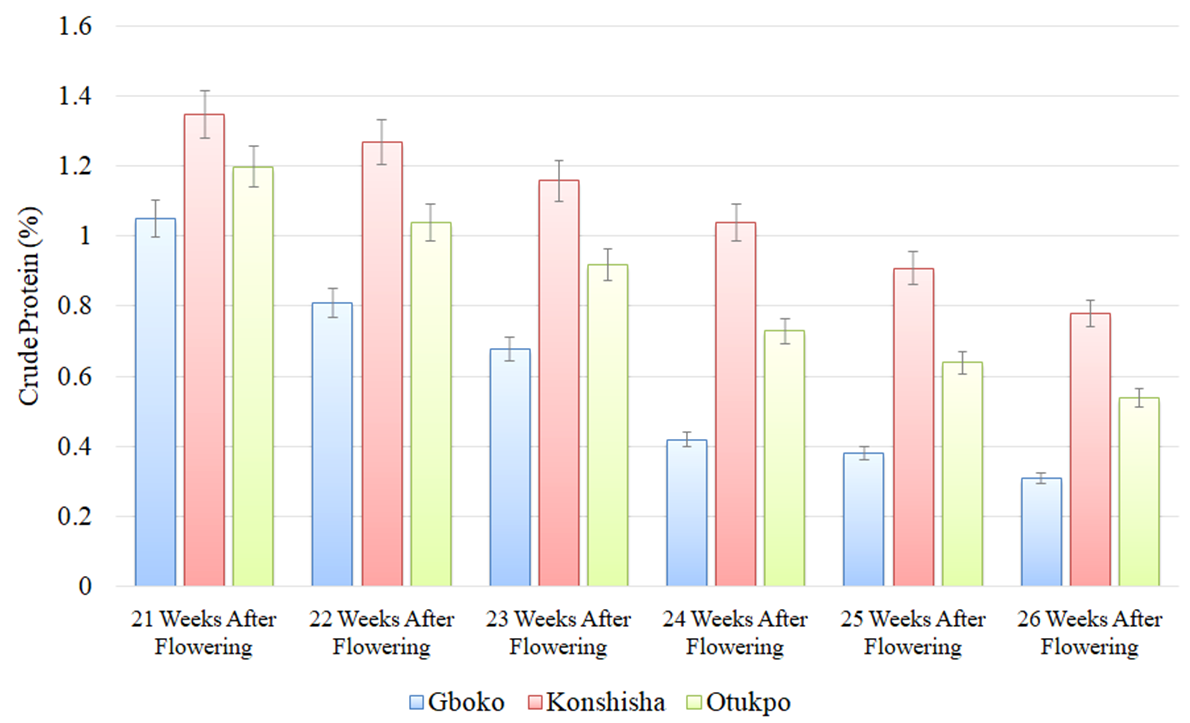

Crude protein on the other hand decreased with increase in maturity stage. Fruits harvested from Konshisha gave the highest crude protein of Mabrouka and the difference was significantly higher than that produced by Otukpo and Gboko respectively. Fruits harvested in Konshisha at 21 weeks after flowering and Gboko at 26 weeks after flowering gave the highest and the lowest crude protein of Mabrouka, respectively (Fig. 2).

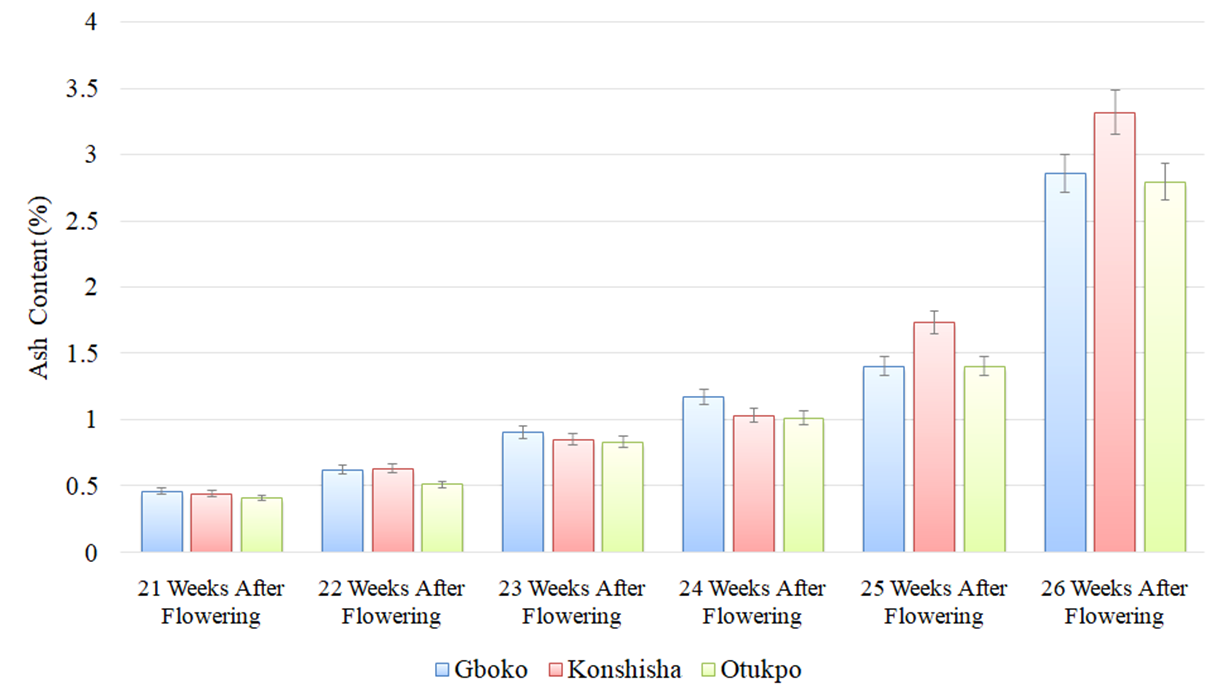

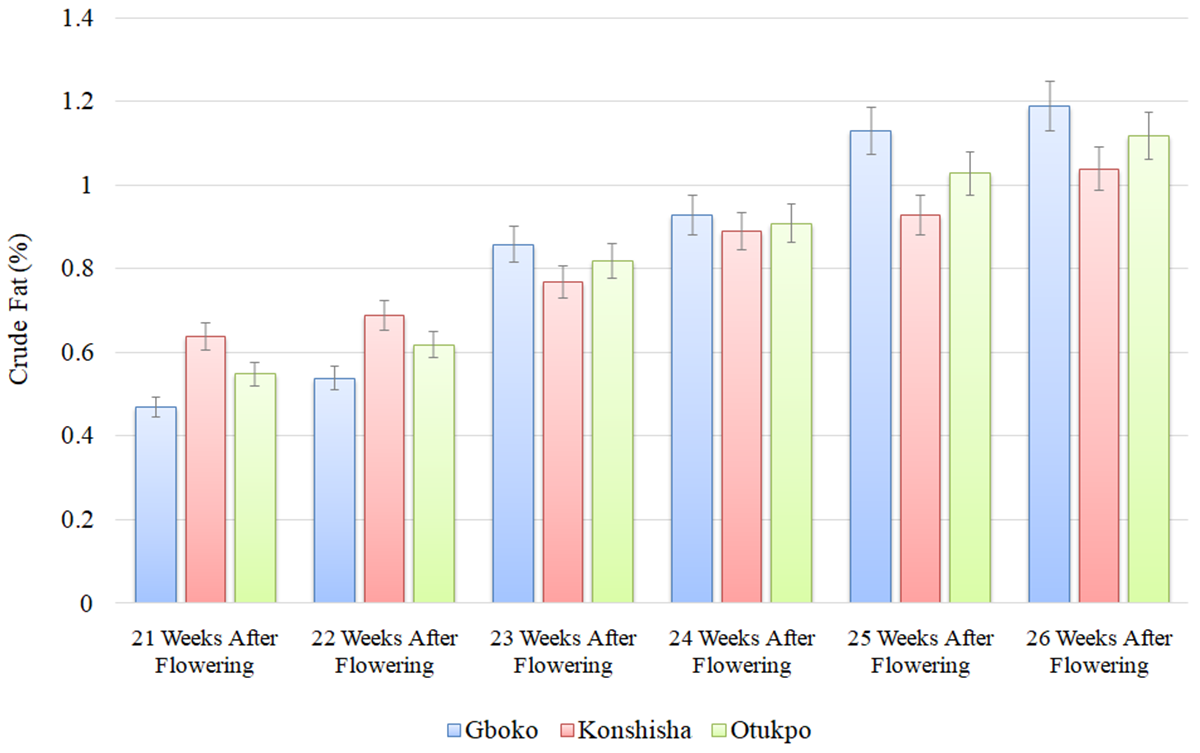

In terms of ash content, a steady increase in values was observed as maturity stage increased. Fruits harvested at 26 weeks after flowering gave the highest ash content among the maturity stages evaluated. Fruits harvested from Konshisha at 26 weeks after flowering gave the highest ash content while those harvested in Otukpo at 21 weeks after flowering gave the lowest ash content (Fig. 3). Crude fat followed similar pattern with respect to maturity stages. With respect to location, fruits harvested in Gboko at 26 weeks after flowering produced the highest crude fat compared to other locations (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1: Effect of location and maturity stage on the crude fibre composition of Mabrouka obtained from proximate analysis in 2018<

Fig. 2: Effect of location and maturity stage on the crude protein composition of Mabrouka obtained from proximate analysis in 201

Fig. 3: Effect of location and maturity stage on the ash content of Mabrouka obtained from proximate analysis in 2018

Fig. 4: Effect of location and maturity stage on the crude fat composition of Mabrouka obtained from proximate analysis in 2018

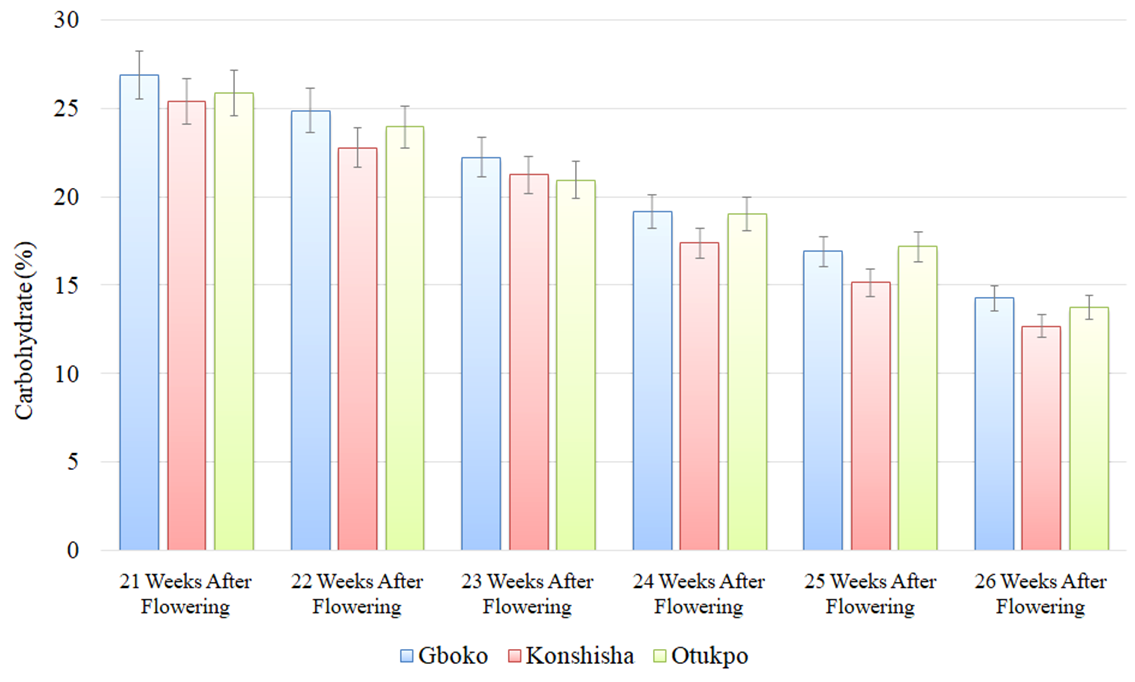

Carbohydrate content of Mabrouka decreased with increase in maturity. Fruits harvested at 21 weeks after flowering produced the highest carbohydrate content of Mabrouka among the maturity stages evaluated. The lowest carbohydrate content was obtained at 26 weeks after flowering. Fruits harvested in Gboko at 21 weeks after flowering and fruits harvested in Konshisha at 26 weeks after flowering gave the highest and lowest carbohydrate content respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Effect of location and maturity stage on the Carbohydrate content of Mabrouka obtained from proximate analysis in 2018

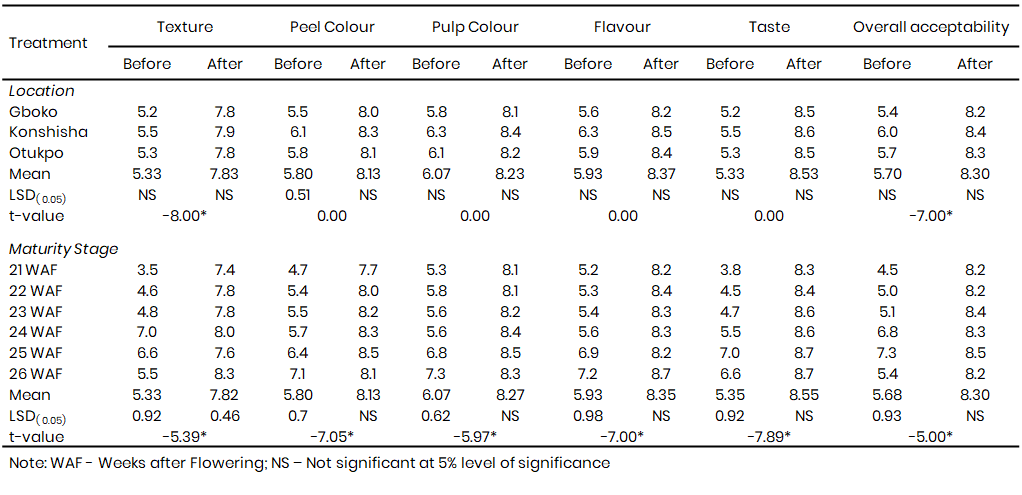

Table 3 shows the effects of location and maturity stage on sensory attributes of Mabrouka mango fruits. The sensory attributes generally did not respond markedly to location except peel colour before storage. In this case, the peel colour of the Konshisha fruits appeared more attractive immediately after fruit harvest compared to the other locations. Fruit maturity stage however, gave a significant influence on most of the sensory attributes evaluated. Generally, sensory traits improved with delay in harvesting of fruits from 21 to 26 WAF, although there were slight variations with respect to individual traits. For instance, the texture of fruits harvested 24 WAF was the best, comparatively. Peel colour of fruits harvested 26 WAF was preferred by panellists. Flavour and taste were best when fruits were harvested 25WAF. In terms of overall acceptability, fruits harvested 25WAF got the highest score. It was evident that all the sensory traits were better when fruits were stored than immediately after harvest, judging from their scores.

Results obtained from the study revealed that location, maturity stage and their interaction affected changes in the fruits biochemical parameters during ripening. TSS was observed to increase with increase in maturity stage. This result is in agreement with the findings of Absar et al. (1993) who also reported that TSS was increased with maturity of mango fruits. TSS is an important factor in the determination of quality in many fruits. A TSS of 13.8% to 17.0% indicates the highest quality of fruits to attain the optimum harvesting stage (Morton, 1987; Kamol et al., 2014). The highest TSS was observed in fully matured fruit (26 weeks after flowering) while it was lowest at the least maturity stage (21 weeks after flowering) evaluated. Normally, as fruit maturity progresses and sugar content increases, total soluble solids will also increase (Rahman et al., 2016; Salamat et al., 2013). The increase in soluble solid contents may be due to hydrolysis of sucrose to invert sugars as reported by Bhatti (1975) and Ullah (1990). The significantly higher TSS value produced in Gboko among the locations evaluated may be due to differences in the soil and climatic conditions of the locations. Lotze and Bergh (2005) reported that maturity indices like TSS are greatly influenced by prevailing climatic conditions and vary from season to season.

Table 3: Main effect of location and maturity stage on sensory attributes of Mabrouka mango fruit before and after storage in Benu

Titratable acidity of Mabrouka ranged from 0.49 to 2.71 and abated with the advancement of maturity. Ambuko et al., (2017) also reported reduced levels of acidity as fruits ripened. Kosiyachinda et al. (1984) stated that titratable acidity decreases with the onset of maturation, however no common value for the maximum titratable acidity exists that could be used to determine the earliest acceptable picking time. In most climacteric fruits, acidity declines as ripening advances (Wills et al., 1989). The reduction in acidity may be due to the degradation of citric acid which could be attributed to its conversion to respiratory substrates required by the cells (Abbasi et al., 2009; Ambuko et al., 2017). Fuchs et al. (1980) stated that the decline in acidity during ripening is as a result of starch hydrolysis leading to an increase in total sugars and a decrease in acidity.

Analysis of variance showed that pH of Mabrouka was significantly affected by maturity stage, location and their interaction. The pH of Mabrouka increased with increase in maturity. This result conforms to the findings of Tridjaja and Mahendra (2000) who reported that the pH of fruit flesh significantly increased with the onset of fruit maturation. Soares et al. (2007) similarly observed that the pH of guava increased during the different maturity stages (Wongmetha et al., 2015). This phenomenon might be possible due to oxidation of acid during maturation resulting in higher pH. In general, young fruits contain more acids that decline throughout maturation until ripening due to their conversion to sugars (gluconeogenesis) (Wongmetha et al., 2015). Gboko produced higher pH values than Otukpo and Konshisha respectively. This could be ascribed to differences in environmental factors.

Results obtained from proximate analysis of Mabrouka showed that the moisture content of Mabrouka was not significantly affected by location and location × maturity stage interaction but maturity stage had significant effect on the moisture content of Mabrouka. As maturity advances, the moisture content of mango also increases. Therefore, the observed increase in moisture content of mango pulp with advancement in maturity was expected. During ripening, carbohydrates are hydrolysed into sugars increasing osmotic transfer of moisture from peel to pulp (Kays, 1991). Crude fibre composition reduced as fruits advanced in maturity. This result is consistent with the finding of Okoth et al. (2013b) who reported a slight decreasing trend with ripening. The decrease in fibre could be attributed to a decrease in insoluble pectin associated with an increase in soluble pectin during the course of ripening (Mathooko, 2000; Mamiro, et al., 2007; Okoth et al., 2013b). The crude protein content of Mabrouka decreased steadily from 21 weeks after flowering to 26 weeks after flowering. Appiah et al. (2011) also observed a decrease in crude protein of mango with advancement in maturity stage. The decrease in crude protein could be attributed to dramatic decrease in the enzymes required for ripening. The crude fat of Mabrouka increased as maturity advanced. This concurs to the findings of Mamiro (2007). The change in fat content on extended maturity could be due to decreased citrate level, which is believed to be the immediate source of acetyl coenzyme A required for biosynthesis of fatty acid and triglyceride (Gomez-Lim, 1997; Okoth et al., 2013b). The increase in ash content of Mabrouka and the decrease in carbohydrate with progression in maturity agree with the findings of Appiah et al. (2011). The increase in ash might be due to differential absorption capacity of different minerals at different stages of development. Decrease in carbohydrate can be ascribed to low levels of sugar, starch and dietary fibres with advancement of maturity. The variation in crude fibre, crude protein and carbohydrate with location could be due to variables like soil composition and climate condition of the area of mango growth.

For fruits evaluated at harvest, sensory panellists preferred Mabrouka fruit texture/firmness at 24 weeks after flowering irrespective of the location. This was reflected in the higher hedonic scale scores obtained at 24 weeks after flowering. For fruits evaluated after ripening, panellist preferred fruits harvested at 26 weeks after flowering. Generally, consumers have preference for firm but ripe mango fruits. As fruits mature, the firmness of the fruit reduces and further declines with ripening. Textural characteristics such as fruit firmness in fruits like mango are more perceived by consumers than other aromatic properties (Johnson, 2000). However, for fruits evaluated at harvest, the preference of sensory panellist with respect to peel and pulp colour and flavour, increased with advancement in maturity. Colour of the skin and flesh is an important quality aspect, which creates the first impression of the fruit on sight to the consumer; it greatly influences degree to which it is purchased for either fresh consumption and/or for processing purposes (Okoth et al., 2013a). Flavour involves the combined effect of acidity, soluble solids and aroma volatiles (Harker et al., 2002). Production of aroma volatiles in mango fruits is linked with metabolism at the later stages of maturity (Fellman et al., 2003) and hence, fruits picked at a more mature stage have relatively high production of aroma volatiles and hence better flavour quality, which is a consumption quality important to consumer acceptability of mangoes (Malundo et al., 1996).

The overall flavor is described as a result of perception by the taste buds in the mouth and the aromatic compounds detected by the epithelium in the olfactory organ in the nose (Rathore et al., 2007; Saeed et al., 2009). Taste preference of Mabrouka increased with increase in maturity up to 25 weeks after flowering then a slight decrease was observed at 26 weeks after flowering but no significant difference was observed between 25 and 26 weeks after flowering. Baloch and Bibi (2012) made a similar observation and opined that fruit taste was developed during the ripening process. As the taste is a combination of sugar and acids present in the fruit, it was expected that the sugar contents were increased and the acid value was decreased with the passage of time (Kays, 1991; Malundo et al., 2001; Baloch and Bibi, 2012). Scores obtained for overall acceptability of Mabrouka showed that people had preference for Mabrouka fruits harvested at 25 weeks after flowering.

Conclusion

From results of the study, it is conclusive that for best sensory traits and TSS, fruits should be harvested 25 to 26 WAF especially when intended for immediate consumption or short distant markets. Fruits intended for long distant markets could be harvested earlier to strike a compromise between quality/acceptability and shelf life.

Conflict of interest

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests

References

Abbasi, N. A., Iqbal, Z., Maqbool, M., & Hafiz, A. I. (2009). Post-harvest quality of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruits as affected by chitosan coating. Pakistan Journal of Botany, 41, 343–357.

Absar, N., Karim, M. R., & Amin, M. A. L. (1993). A comparative study on the changes in the physicochemical composition of ten varieties of mango in Bangladesh at different stages of maturity. Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Research, 18, 201–208.

Ambuko, J., Ouma, L., Shibairo, S., Hutchinson, M., Njuguna, J., & Owino, W. O. (2014). A comparative evaluation of maturity indices of mango fruits produced in two contrasting agro-ecological zones of Kenya. Fourth RUFORUM Biennial Regional Conference, 21–25 July 2014, Maputo, Mozambique, 261–266.

AOAC. (1995). Official methods of analysis (16th ed.). Association of Official Analytical Chemists.

Appiah, F., Kumah, P., & Idun, I. (2011). Effect of ripening stage on composition, sensory qualities and acceptability of Keitt mango (Mangifera indica L.) chips. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 11, 5–10.

Bally, I., Lu, P., & Johnson, D. (2009). Mango breeding. In S. M. Jain & P. M. Priyadarshan (Eds.), Breeding plantation tree crops: Tropical species. Springer Science & Business Media.

Baloch, M. K., & Bibi, F. (2012). Effect of harvesting and storage conditions on the post-harvest quality and shelf life of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit. South African Journal of Botany, 83, 109–116.

Barreto, J. C., Trevisan, M. T., & Hull, W. E. (2008). Characterization and quantitation of polyphenolic compounds in bark, kernel, leaves, and peel of mango (Mangifera indica L.). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 56(14), 5599–5610.

Bhatti, M. S. (1975). Studies on some ripening changes in mangoes during storage (Master’s thesis). University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan.

Brecht, J. K., Yahia, E. M., & Litz, R. E. (2009). Postharvest physiology. In R. E. Litz (Ed.), The mango: Botany, production and uses (2nd ed., pp. 484–528). CABI.

Copyright

Open Access: This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.